- Home

- Rachel Lloyd

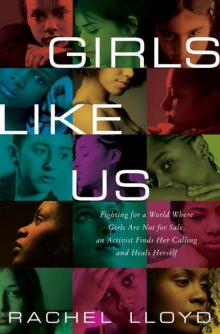

Girls Like Us Page 8

Girls Like Us Read online

Page 8

The first few weeks in her new home were the best time of Tiffany’s twelve years. He took her shopping and bought her new sneakers, jeans, shirts, and even a pair of high heels and a sexy dress. Tiffany had never had so many nice things and for the first time she didn’t have to hide new clothes from other girls in the group home who would surely steal them. She felt like a proper grown-up housewife; she cleaned and cooked and they had sex every night. Life in the group homes had taught her cooking skills, and Charming appreciated her lovingly prepared meals each night after he came home from a long day of hustling crack on the block. Life was perfect to Tiffany; she doodled their names everywhere, Tiffany loves Charming in big loopy letters with love hearts complete with arrows through them. She figured that he would marry her when she turned sixteen, in four years, so she practiced saying Mr. and Mrs. Jackson in the mirror.

Charming encouraged her to dress more grown-up and liked her to dance in underwear and high heels for him. At first she felt shy and awkward but he coached her gently, showing her how to shake her butt, undress in a sexy way, and when he was finally pleased with her performance, she felt so proud. One night, Charming came home and didn’t want dinner; he seemed in a hurry. He told her that he wanted her to go to the club with him; he even picked out the sexy dress and high heels. He said it was a different type of club so they had to make a good impression. He gave Tiffany two glasses of Hennessy before they left the apartment, but Tiffany was buzzed enough on the feeling of going out with her man for the night to really feel the alcohol.

When Tiffany awoke slowly the next morning with a pounding headache, she had only a vague recollection of the night before, and as the thoughts of dancing, of men, of stripping flooded into her mind, they made her head hurt worse. Charming was on the side of the bed counting money happily. “Damn baby, that ass sure makes a lot of money.” He looked so proud, Tiffany couldn’t bear to tell him that she didn’t want to do it again.

As Tiffany, now a tired sixteen-year-old, sits telling me how it all began, I can picture her, smiling at Charming, grateful for the attention. I can imagine the details, fill in some of the blanks, and while it’s the first time that I’m hearing her specific story, it’s all too easy to imagine because, save for a few details, it sounds pretty much like every other recruitment story I’ve ever heard.

Elizabeth tells me that she just knew her man loved her when he took her to a fancy restaurant. Where, honey? Red Lobster. After that, she thinks she owes him, so she does whatever he tells her to do.

Tanya’s mother, an alcoholic, won’t buy her the new Barbie. She hops a train into Manhattan to buy it herself at FAO Schwarz with her savings. Lost in Times Square, Tanya meets a man who says he’ll help her. He takes her to the track that night. She’s eleven years old.

Bethany’s mother sells her for drugs on the street. When she starts junior high school she discovers that she’s been sold to some of her own family members. Humiliated, she runs away and meets a guy who picks up where her mother left off.

Ashanti thinks that the cute guy she meets in a homeless shelter is her boyfriend. They decide to hunt for an apartment together, but are approached at gunpoint by three men who force them into a car. She thinks they’re being robbed but then she realizes that he knows these guys and is part of the plan.

Shana’s a quiet, studious, sheltered twelve-year-old when she meets a twenty-two-year-old who wants to be her boyfriend. She loses her virginity to him. He puts her out on the track. She says she’s in love.

Alina watches her mother walk around the neighborhood offering her body in exchange for crack and then later watches her slowly dying from AIDS as the neighborhood shuns her. When she meets a pimp, it doesn’t seem that bad by comparison.

Jessica is sixteen when she moves from North Carolina to live with an aunt who’s just met a new man and doesn’t want Jess there anymore. After she’s kicked out, Jessica sleeps on the train for a few nights and eventually starts sleeping with men who feed her and let her stay over. It seems like a good idea to get a pimp for protection.

Maria is homeless due to her mother’s schizophrenia and continual instability. She meets a guy who takes her in and sets her up in his mother’s basement. He starts bringing guys in and forces her to strip for them. He’s frustrated that she’s too young at twelve to know how to dance “sexy” enough, so he teaches her.

It reminds me of a macabre version of the Choose Your Own Adventure books: A few options along the way will ultimately lead to one of not many outcomes. If you chose running away from your mom, skip to page 6, where you’ll meet a pimp at the subway. If you chose running away from a group home, skip to page 7, where you’ll meet a girl who’ll introduce you to a pimp. If you’re homeless and feel like you to have to trade sex in exchange for a place to sleep that night, jump ahead to page 15, where you’ll be living with a guy who now sells you every night. There’s no grand prize at the end of these stories, though, no reward. Just a few minor variations on the same theme—vulnerable meets predatory; abused child meets billion-dollar sex industry. Not hard to guess the ending.

Recruiting a vulnerable girl isn’t hard either. As Lloyd Banks so aptly states in the remix of 50 Cent’s platinum-selling song “P.I.M.P.,” “I ain’t gotta give ’em much, they happy with Mickey D’s.” Teenage girls, especially those who’ve already been abused, who are living in poverty, who come from fractured families, are relatively easy to lure and manipulate. In fact, despite 50 Cent’s argument that the song is referring only to adult women being sold (presumably less disturbing), it’s hard to picture an adult woman, unless she is literally homeless or starving, being “happy with Mickey D’s.”

Yet having worked with preteen and teenage girls for thirteen years, I know that nothing causes greater excitement than announcing a trip, especially in my car, to McDonald’s. Like Elizabeth, who was wooed by her concept of fancy dining, teenage girls’ culinary standards are relatively easy to meet. So are their standards for what qualifies as love, particularly for girls whose whole definition of love has been grossly distorted by the relationships they’ve seen growing up and the abuse that they’ve been told equals love. It doesn’t take a lot: a good nose for sniffing out vulnerability, a little kindness, a bit of finesse, paying attention to the clues she gives away about her family, her living situation, her needs. Once he’s got the hook in, a few meals, rides in his car, perhaps an outfit or getting her nails done can seal the deal. She thinks he cares. She wants to please him. It doesn’t really matter how he introduces the topic, whether he gets her drunk and takes her to a strip club, cries broke and asks her to do it “just this one time,” beats her into total submission, has his other girls encourage her that it won’t be that bad, or spins the promises of a better future, money, security, being “wifey,” the end result will be the same. He knows that once she crosses that line for the first time, it’ll be hard to go back. It might take a day and cost nothing, it might take a few weeks and cost a few dollars, but ultimately the investment he puts in will be worth the return. Even if he strikes out with a few girls who are perhaps not quite as vulnerable as he first assumed, it doesn’t really matter—there’s always another girl right around the corner. In fact, pimping is really an economist’s dream, a low-risk, low-investment, high-demand, high-income industry. Indeed, there are many pimps who are smart, shrewd, and calculating “businessmen,” but this concept does beg the question of how shrewd you really need to be to lure a fifteen-year-old who has run away from abuse at home and is currently spending the night on a train.

Some of the girls, however, have been forced into the sex industry through kidnapping and violence, held at gunpoint, pushed into a car, kept in a locked room. Girls are then raped, often gang-raped initially, to break their will. The subsequent shock and traumatic response leave the girl feeling utterly helpless and totally subdued. The fear often keeps her from running away. The shame can keep her from reaching out for help. While it can be shocking for people to

initially learn that American girls, ones who never, ever make the news, are kidnapped with increasing frequency, these are still, relatively, the cases that tend to engender the most public sympathy and interest from the criminal justice system. Their victimization seems obvious and fits into a tidier, more common understanding of human trafficking.

Yet for most of the girls, the force, the violence, the gun in her face don’t come until later. Their pathway into the commercial sex industry is facilitated through seduction, promises, and the belief that the abuser is actually their boyfriend. Statistics show that the majority of commercially sexually exploited children are homeless, runaways, or the distastefully termed “throwaways.” These girls and young women have a tougher time in the court of public opinion and in the real courts of the criminal and juvenile justice systems. It is presumed that somewhere along the line they “chose” this life, and this damns them to be seen as willing participants in their own abuse.

WINTER 1993, GERMANY

It’s been three weeks and my money has dwindled down to about eight dollars. Eating for under a dollar a day may be possible in some countries but not in Germany. Nicotine, the good old appetite suppressant, has helped with the hunger pangs, but I barely can afford cigarettes now and I’m rationing them out to myself like a jailbird. Leaving England with girls I’d known for one evening on a one-way ticket, and believing that my ex-boyfriend would be so heartbroken that he’d send for me within a few weeks, doesn’t seem to have been that great a plan. The girls are caught up in their own stuff, and have milked half of my money in the process. My ex informs me coldly by phone one night that yes, he was cheating and she’s moved into my place and a one-way ticket really does work only one way. There are other unforeseen challenges. Not speaking German is proving a bit of a hindrance. Not being legally old enough to work, another roadblock. Bringing only enough money to last a couple of weeks? Strike three. I’m stuck. Stucker than I’ve ever been in my life. It’s a tight jam when you’re in London with no money and no way home, but if you live in Portsmouth, it’s just three hours away. Stuck in Munich with no money and no way home is another story. Desperate times call for desperate measures.

It’s late afternoon and I’ve applied for, begged for, cried for any type of employment at all the four million restaurants and bars in Munich. Having attempted to find work at all the major hotel bars and decent-looking restaurants, I’m down to crappy cafés and pay-by-the-hour motels. Rejection from places that look as if they’d be fortunate to get a visit from the health inspector let alone a guest is hard to swallow. I’ve gone full circle around the city on the U-Bahn and have ended up back at the Bahnhof, the main railroad terminal, where the streets are filled with clubs and bars. The streets are thriving during the day, although the glowing Girls, Girls, Girls signs are faded in the winter sunlight. The street seems less seedy, less threatening in the daylight, and as I stare at the Girls sign, a startling revelation hits me. I’m a girl. Although this may not be the most profound epiphany I’ve ever had, the Plan is beginning to formulate in my head, even as I walk toward the sign and into the entrance of the club. I’m moving too quickly to think it all the way through to a sensible conclusion, but the outline goes something like, This is a strip club, girls dance in strip clubs, they pay girls to dance, I’m a girl, I can dance, I need money, they probably need girls, therefore I will dance to make money. Even as this genius hits me, the other side of my brain is protesting loudly, although apparently not loudly enough. It’s only for a couple of weeks, I’ve done nude modeling before, illegally of course given my age, and I’ve been a dancer in regular nightclubs, so combining the two shouldn’t be that hard. It’s not that bad, just a few weeks, go home and forget the whole thing. I work so hard to convince myself that I’m sure my lips are moving. I walk down a long hallway, dark and painted red, and down a flight of stairs into a huge, empty club.

It takes an altered date of birth on my passport and about four minutes to get hired as a “hostess”—starting immediately, cash same day. It’s too good to be true. Get paid to sit at a bar and drink? I already drink like a fish, or more accurately like my mother. This will be an easy job. My tired, hungry teenage mind wants to believe that drinking with the customers is really all there is to it. And with the first customer that’s all I’ll have to do. But by the end of my first shift, I want to scrub my skin off, even though I’ve earned more that night than any of those shitty cafés would’ve paid in two weeks. In a gesture of celebration that I don’t really feel, and because I’m drunk, I use ten marks of my day’s earnings to catch a cab home. Out of the club, in the cold air, the black line feels blurry. I feel like everyone’s looking at me, everyone knows my dark and dirty secret, which I want to stay hidden behind the door of the club. Driving in the cab, I watch women on their way home from work, on their way to a date, and I feel like a voyeur into the normal world. I haven’t crossed “The Line,” but I’ve crossed a bunch that I thought I never would. Still, plenty of men have touched me when I didn’t want them to; none of them has paid for the privilege. I figure I can keep some boundaries given that I’ll be at the club only for a few weeks, three tops. Get enough money to pay the rent, buy a ticket home and never, ever, ever tell anyone what happened. That night, I buy food and pay the rent before I get evicted. The next day I pile on the makeup, give myself a whole different look, change my name, and go back to the club. The more distance I can keep between Rachel and this other person who just needs to survive right now, the better. But the Line keeps moving and the boundaries keep blurring and it’ll be a long time before I see Rachel again.

In recovery, as an advocate and running GEMS, for a long time I’ll feel guilty about the way I entered the sex industry. In a radio interview one day, an abrupt interviewer who keeps calling me an ex-prostitute objects to my correction and use of the term “commercially sexually exploited.” “Well, you were older, so obviously you made a choice,” she declares. I object again, but her accusatory and judgmental pronouncement stings. A few moments later when she calls my girls “ghetto girls,” I let her know in no uncertain terms that I’ll be terminating the interview, and hang up on her. I recognize that she’s rude, obnoxious, and racist, but still, her earlier comments bother me. Obviously you make a choice. As I struggle with it that night, I concede that yes, I made a choice. No one put a gun to my head, unlike Samantha, who was snatched off the street as she walked home from school. I was seventeen, not twelve, thirteen, or fourteen like Maria, Crystal, Briana, Simone, Kei, Tionne, or thousands of other girls I meet, who are so young, so clearly children, so naive regardless of their supposed “street smarts” that it’s unconscionable that anyone could ever suggest that they deserved this or wanted it. I wasn’t lured by a pimp; in fact, I won’t meet mine till several months later. No one forced me, coerced me, or even pressured me. I made a choice. I reflect on this over the years, and struggle with the implications of this choice and what this makes me: stupid, loose, greedy, lazy, sluttish; the list of words I’ve used to judge myself goes on and on. I listen to myself try to help girls to forgive themselves and alleviate their profound sense of shame. “Whatever you thought you had to do to survive or to stay alive, it’s OK.” It’s easier, though, to see the girls’ age and circumstances and recognize that they didn’t have a choice than it is to see my own vulnerabilties and lack of choices. It’s only as I get older that I’m able to extend to myself the same grace and compassion that I freely give to the girls. Only later can I give my scared teenage self a break and understand with compassion for myself how the “choices” I made were limited by my age and circumstances, and my lack of insight about how hard it would be to leave after just a couple of weeks.

The question of choice impacts the way that domestically trafficked girls are viewed and treated by our society. Many people believe that girls “choose” this life, and while it is true that most girls are not kidnapped into the sex industry, to frame their actions as choice is at best misleadi

ng. It is clear from the experiences of girls that, while they may have acted in response to individual, environmental, and societal factors, this may not necessarily be defined as a choice. The American Heritage Dictionary describes the act of choosing as “to select from a number of possible alternatives; decide on and pick out.” Therefore in order for a choice to be a legitimate construct, you’ve got to believe that (a) you actually have possible alternatives, and (b) you have the capacity to weigh these alternatives against one another and decide on the best avenue. Commercially sexually exploited and trafficked girls have neither—their choices are limited by their age, their family, their circumstances, and their inability to weigh one bad situation against another, given their developmental and emotional immaturity. Therefore the issue of choice has to be framed in three ways: age and age-appropriate responsibility, the type of choice, and the context of the choice.

The age factor is perhaps the most obvious reason that discussions about true “choice” are erroneous and unhelpful to the debate. There’s a reason that we have age limits and standards governing the “choices” that children and youth can make, from drinking to marrying to driving to leaving school, and it’s because as a society we recognize that there’s a difference between child/adolescent development and adult development.

This is also why the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 and its reauthorizations in 2003, 2005, and 2008 have all supported a definition of child sex trafficking where children under the age of eighteen found in the commercial sex trade are considered to be victims of trafficking without requiring that they experienced “force, fraud, or coercion” to keep them there. For victims of sex trafficking ages eighteen and over, the law requires the “force, fraud, or coercion” standard. In defining the crime of sex trafficking, Congress created certain protections for children. It’s taken as a given that children and youth are operating from a different context, especially in light of age of consent laws.

Girls Like Us

Girls Like Us