- Home

- Rachel Lloyd

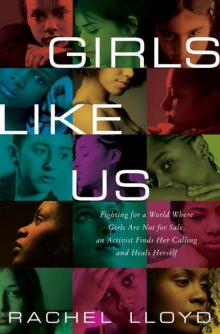

Girls Like Us Page 23

Girls Like Us Read online

Page 23

Just like there are some people who are able to use cocaine regularly without jeopardizing their careers, some people who are able to drink and drive without causing an accident, and some people who are able to fight in a war without suffering from PTSD, there are people in the sex industry who may not have suffered any harm. But just because an individual experience has not been difficult, painful, or disempowering doesn’t make it true for millions of women and children around the world. The sex industry isn’t about choice, it’s about lack of choices. It’s critical for children and youth, and even for many adult women within the sex industry, that we use language that frames it accurately.

After a week of turning down numerous media requests from reporters salivating at the chance to interview an ex-prostitute at the height of Spitzer-coverage frenzy, I agree reluctantly to go on a 20/20 special with Diane Sawyer. Although I hate to watch myself on television (Why didn’t I realize that my eye makeup was too dark? Must they use a graphic of stilettos when introducing me?), I find myself getting caught up in the program itself as they show woman after woman on the streets and in the brothels of Nevada, women whose pain seems to reach through the TV and punch me in the stomach. Here was I, in my carefully applied makeup and “official” black suit, with the title card as I’d carefully instructed to read Rachel Lloyd, Executive Director, GEMS, commenting as an “expert” on the perils of life on the streets, in a segment next to “Kayla,” who pulls up the back of her shirt to show Diane Sawyer a one-hundred-stitch scar courtesy of a john; Tina, who was once, not long ago, studying music in college, until heroin introduced itself into her life; Brandi, who while a “top earner” at the Bunny Ranch breaks down during an interview; Sarah, who lives in a squat with no running water.

As I watch and listen, with unbidden tears streaming down my face, I know exactly what Tina means when she said she counted in her head through each trick to take her mind off it, what Brandi feels when she hugs the pillow and sobs. Their pain feels so close, so almost yesterday, the memories of counting, of crying, so visceral. I feel the same love for these women that I feel for the girls at GEMS, the same love that comes from a shared experience of a very specific type of hurt and shame that, deep down, will always be a part of me. In my little West Elm–decorated apartment, with my car parked in the garage outside, my two degrees, my ten years of experience in the field, I remember what it really felt like.

As I cried for them, for my younger self, and with gratitude for who I had become, I felt shame welling up. Had I worked so hard to be “more than a survivor” that I’d lost track of what being a survivor really was? Was I so caught up in how far I’d come that I’d forgotten exactly where it was that I’d started? I’d let the media frenzy over “hookers” and “whores” make me want to hide that part of myself, that part I shared not just with these women but with my girls.

I reminded myself how blessed and lucky I was to have people who’d told me that I deserved better, that I didn’t have to live in shame all my life. I wondered how I’d been so fortunate, and thought of all the people who had supported me and loved me and helped me heal, and yet my biggest critic, my harshest judge, had always been myself. It was my own voice that for years had shamed me and called me names, and it had been my own internal shame that I’d had to deal with. Over the years I’d learned that somewhere along the line, you had no choice but to accept what had happened; place the blame where it lay, understand the larger social forces, the twists of family and circumstance that had left you vulnerable in the first place. It was ultimately the acceptance, the integration of your experiences into the much larger narrative of your life, that kept you in a place of recovery, that gave Toni’s brother and the Jeffreys and the rude reporters of the world less room to hurt you.

I realized that it was owning what I’d been through, not hiding it, that had opened the door to real healing for me. I’d challenged people’s expectations of what a sexually exploited high school dropout could do with her life, and in doing so reminded myself that I was more than anyone else’s judgments about me. I prayed that night that Tina, Brandi, and Sarah would have the opportunities to escape, to heal, and to not allow the world around them to tell them that they were tainted, irreparably damaged, that their voices didn’t matter, or that no one was listening.

Chapter 14

Healing

A father of the fatherless, and a judge of the widows,

is God in his holy habitation.

God setteth the solitary in families:

he bringeth out those which are bound with chains.

—Psalms 68:5–6

SUMMER 1997, GERMANY

I wake up ready, but instead of bouncing out of bed, I lie there, savoring my last morning in Germany. This time tomorrow I’ll wake up in another country and begin another life. I have no idea what to expect about New York, but I’m excited to start anew somewhere else. Still, my chest hurts at the thought of leaving this place. It was here to this airbase that I came three years ago, barely functional and a broken mess of pain. The airbase has functioned as a cocoon of safety and healing for me, and I’m leaving as an almost unrecognizably different young woman. To me, the military base is beautiful with its rows and rows of neat housing, manicured lawns, dads washing their cars, kids playing out front, and neighborhood barbecues in the summertime. There is no visible poverty, no obvious drug addiction, no homelessness. Everyone is within a certain income level, a specific age bracket, and other than a few bored high school kids who attempt to be daring with their goth or gang member looks, everyone pretty much looks the same, a dubious mix of sporty and JCPenney. Even the apartments all seem to have been furnished by the same decorators, with hideous entertainment units and all the bathrooms decorated with either the Hunter Green or Seashells matching towel sets sold at the PX.

I have, however, grown to recognize that behind the Rockwellian lawns and curtains lies a darker picture of constant infidelity and, often, domestic violence. With the recent advent of the Bosnian crisis, young soldiers and their families who had known only military life in peacetime are now facing separations and fears that the recruiter never informed them about. Yet despite it all, I still love it. The order is comforting, especially in the wake of my turbulent and disordered past. I conform quickly. I decorate my room, choose some of my church wardrobe from the JCPenney catalog, eat Hamburger Helper and processed ham with Wonder bread and mayo, wear socks with my Birkenstocks, and love anything Nike. I am finally just like everyone else. Even though I see beneath some of the facade, most of the time I don’t want to. I want to stay in this community, where violence is no longer a part of my life. I have a strong attachment to the base, a place that’s come to represent and symbolize so much to me, but ultimately it’s thinking about the people I’ll miss that makes my chest feel like its crushed with grief.

I lie there watching the clock knowing that in a few hours I’ll be gone, and tears soak my face. I wish I could say all my good-byes one more time, but I’ve said them all, other than to the family taking me to the airport.

Cheryl and Samantha, the other nannies with whom I’ve shared never-ending cups of tea and chatted with about our romantic lives and the gossip on base while “our kids” played together, have both already left for the States. Cheryl left with her boss and was going to continue being a nanny, and Sam was marrying a soldier. Without their adult conversation and support, being a nanny is a little less fun, and I’ve already begun feeling their absence. One of the challenges of living on a military base is that someone’s always leaving.

Finally, I’m the one leaving, having a yard sale with my stuff. I’ve spent the week making my rounds, taking hundreds of photos, crying and crying and promising to stay in touch forever and ever. Leaving church was perhaps the hardest, despite the fact that my move has been with my pastor’s full encouragement and blessing. I don’t want to leave the comfort of Victory Christian Fellowship, the place where I’ve experienced the kind of peace and overw

helming love that I’ve never felt anywhere else and where I’ve begun to believe that perhaps God really does love me. It’s been through the compassion of many of the people at church that I’ve seen that love put into action, as I’ve been given clothing, a job, a place to live, and hours and hours of patient counseling and support. Although I’ve never fully shared my past, most people know that I’ve been through some “stuff” and have treated me with great kindness and gentleness. My pastor, and some of the other men in the church, have modeled for me what a “real” man acts like, and I’ve been shocked and relieved that none of the men, at least the married ones, has ever even come close to stepping across any of my blurry boundaries. In the beginning, I’d even had a crush on my portly, bald pastor, so struck was I by his kindness, intelligence, and obvious devotion to his wife. I’m sure he notices, and the way that he ignores my misguided affection turns into deep respect. He teaches the Bible in a way that I can understand and that doesn’t feel misogynistic or disconnected from social justice. I’ve grown enough at the church that I’ve moved from hanging out with the little kids in order to hide my severe shyness to becoming the director of the children’s ministry, the youngest person ever in the church to be in a leadership role. It feels like the greatest honor of my life and I take it very seriously, probably a little too seriously, if my volunteers were polled. I’m so nervous about being in charge of adults and still so painfully shy that I’m an awkward leader. But I excel at coming up with creative ideas for lesson plans and ways to better the ministry. My role has helped my confidence a little, although I’m still a horrendous public speaker and my good-bye speech consists of four mumbled words and more crying.

It’s even harder to say good-bye to Dr. Hall, a guidance counselor at the high school where I’ve been volunteering for over a year. She has helped me discover my passion for working with teenagers and allowed me to recognize that I have an instinctual talent for counseling and creative ideas for programs. When I’d originally approached the vice principal with the idea of volunteering, despite the fact that I’ve never finished high school myself, neither he nor I had a clue what I’d end up doing. I couldn’t type, I’d never filed, and I had horrific computer skills. In the face of my earnestness, he reluctantly pawned me off onto Dr. Hall, who within a couple of weeks was giving me Reviving Ophelia and a stack of other books about adolescent girls to read. I spent over a year working individually with almost every student in the school on a computer program that helped them identify careers and colleges of interest. For the first few months, I’d pretend to need to go to the bathroom at the beginning of the first day’s session and casually ask the students to turn the computer on. Fortunately no one ever figures out that I actually don’t know how to turn the computer on myself, and after a few months I pick up some basic computer skills. Learning new skills and finding out that I’m reasonably competent at a lot of different things is exciting for me. What started out as something to do for a few hours a week, now that the children I was babysitting were in school, had become almost a full-time job, in addition to the part-time job I held as a cashier at the PX. The principal even offered to create a full-time paid position for me at the school so I could continue this work, a level of validation for my efforts that I don’t expect. Throughout the year, it became clear to me that there were students who were chronically absent, and I asked Dr. Hall if I could spend some time focusing on them. In uncovering the reasons behind these students’ absenteeism, I’m drawn into more complicated issues: teen parenthood; a girl who’s been gang-raped by several soldiers and I’m the first person she’s told; a girl whose mother has left and who is now developing into a full-fledged alcoholic under the absent gaze of her father. It’s these girls that I connect with, rack my brain to think of creative ways to support, and learn some hard lessons with, e.g., never promise that you’ll keep a secret without knowing what that secret is first, particularly when it’s something like rape that you’re required to report to the authorities. Dr. Hall has been my first professional mentor, before I even knew that I needed one, and she has given me so much space to grow that I’m scared of doing this work without our daily check-ins. She tells me she has total faith in me and writes me a beautiful recommendation letter that I read over and over again.

I’ve been a nanny for the Petersons for the last two and a half years and have loved their three children like my own. Bernadette, a matriarch in every sense of the word, has been like a second mother to me. I’ve cried and prayed with her many times, learned to cook the best southern food under her tutelage, and tried my best to emulate her as a woman. With her own history of abuse, she’s taught me to look in the mirror every day and tell myself that I’m lovable and valuable. She’s challenged me to accept love when I didn’t even know I was rejecting it. The family has treated me as their own, with Harold even telling people that I’m their oldest daughter, despite the fact that they’re black and I’m obviously not. I’ve learned what it is like to be part of an actual family. We’ve gone to church together, spent holidays together, gotten on each other’s nerves, and ultimately loved each other. When I began dating, they even set a curfew and Harold tried to vet each suitor like a proper father. I bristled against this level of interference, but in some ways I liked the idea of being cared for in that way, even if it was about eight years too late. I’ll miss the kids the most and I spend as much time with them as possible before I leave, hugging them tightly, hoping they’ll remember me.

The date that Harold doesn’t meet is the one I’m most infatuated with. Sam lives in the building behind mine, and is the boy epitome of my feelings about the airbase and its barbecues and lawns. My desire for a normal, suburban family experience translates into the desire for the type of normal teenage relationship that I never had. We don’t have a lot in common and most of the time we talk awkwardly about nothing, but I don’t care. Our dating life is relatively chaste and boring, which I love. We watch movies, sometimes at his house till his mother and father come home and make it clear that I need to leave. Sam goes to the prom with another girl that he’s seeing and I’m crushed. It’s hard for me to accept that I’ll never recapture my teenage years, and I don’t speak to him for several weeks. I watch him play football from afar and pine away in teenage-girl fashion, writing his name all over my notebook.

Just before I leave, having kissed and made up, Sam and I take a trip to Mainz and walk along the river. It feels fitting to be back in Mainz where so many terrible things happened to me, but this time with my safe and sometimes boring crush. He takes me to McDonald’s for my good-bye dinner and the thrill of a “teenage” relationship is beginning to wear off. We pose arms wrapped around each other and ask a passerby to take a picture. I’m disappointed several weeks later when I discover that the picture doesn’t come out, but even without the photographic evidence, the image is clear in my mind, me in my pink and white floral dress, him in his ever-present uniform of black T-shirt and jeans, the backdrop of the Rhine at dusk behind us.

I know that I’m about to embark on a whole new chapter and that I won’t ever really come home again, not to this time and place. But I’m ready. Bernadette, Harold, Dr. Hall, Sonia, my pastors, the folks at church, Samantha, Cheryl, and even Sam have given me a sense of hope and a sense of self. They’ve been my family, the community where I’ve been able to hide and heal, at least enough to keep moving forward. On a small airbase in Germany they’ve accomplished a miracle. They’ve loved me back to life.

In psychologist Abraham Maslow’s oft-cited Hierarchy of Needs theory, the need for social connection, for community and belonging, are a critical part of any individual’s well-being and development. Once the initial needs for shelter, food, resources, and safety have been met, there remains a deep human need for friendship and family, and beyond that, for competence, mastery, and respect for and by others. I hadn’t heard of Maslow’s theories until I came to New York and studied Pysch 101 in college. Yet I understood that the love

and support from the adults around me, the total acceptance and physical affection from my little kids, the ability to try new things and develop skills by volunteering and working, had enabled me to begin my healing process and had left me with a new sense of myself and my abilities.

Most girls, though, aren’t fortunate enough to have a sleepy little military base replete with a built-in community to help with the recovery process. They’re often still in the same communities, perhaps just a few blocks away from where they were first trafficked, often dealing with many of the same challenges that made them so vulnerable in the first place.

Trafficked girls are also getting many of their needs met in the life, albeit in the most distorted and exploitative fashion. In addition to the basic needs for sustenance and survival, pimps provide a sense of belonging to a family. Being good at making money feels like a level of competence and mastery, and having daily attention from johns can feel like a boost to your self-esteem, even though it’s based solely on your ability to provide sex. If you’re going to take something away, you have to replace it with something else. Trafficked and sexually exploited girls and young women need a place to hide and heal, but it is not enough to solely provide for their basic needs of food, shelter, and clothing. As I began to create GEMS, I understood that they also need a place where they could feel like they belonged, where they could feel strong and empowered, a place where they could feel loved and valued, even as the struggles remained right outside the door.

Girls Like Us

Girls Like Us